| Abstract |

CHAPTER 1

THE TANG OF SEA AIR

Page 1

If you can imagine life without piped water, sewerage, gas, electricity, street lighting, motor transport, Radio, television, strawberry-flavoured toothpaste, then you already have a fair idea of the little world I was born into. Circa 1795, oh no! to be more precise, April 1909; and had I known what I was letting myself in for, I'd probably swiftly hurried back from whence I came, as being the safest and most carefree haven I'd be likely to have since assuming human shape. Fortunately, it isn't an event we are under any obligation to be grateful for, but at least, the spring is as good a time to start as any. The actual physical projection was certainly unaccompanied by any pre- or post-natal "hoo-ha". Mother had a couple of precursory examinations by the homely old country doctor, who drove from his residence several miles away on the mainland, his vehicle was a light, Two wheeled, rubber-tyred cart, drawn by a patiently willing light brown horse. The latter philosophically accepted its role; after all, it was more congenial than dragging a milk float. The placid old medico was readily recognisable by the hallmark of his

profession, a neat, black Gladstone bag. Whether you were the family's first or tenth addition to the local

population, the procedure was invariable; after his paternalistic examination, he'd murmur reassuringly, "You'll be alright, Ma'am. A gentleman and natural psychologist, he addressed the humblest of his female patients as Ma'am. He knew instinctively that each of them liked to be treated as a lady, also it instilled confidence. He also knew quite well that he was truly in the lap of the Gods when it came to getting his fee in his somewhat impoverished rural domain. The fact that he employed a maid and a gardener-cum-groom in his imposing Georgian house seemed to imply that the majority of his patients must have paid him eventually. Not that he made any distinction between those that pat that night.

When it came to "delivery-time" we were fortunate, inasmuch that the "midwife", a kindly and efficient old sole, normally worked for the dairy farmer opposite, as a maid-of-all-work. It's likely that she helped to deliver the calves as well, for these can often prove more "difficult' than human progeny. She was a petite, quiet, unassuming old spinster, who invariably wore a black dress with a hand-crocheted lace collar; worked with her own small, toil-worn hands, I'll be bound. Reputedly, she'd never had a day's hospital training in her life. I recon she took a secret pride in the fact that she'd assisted the majority of the village's youngsters into the world without mishap. In later years, I often had to take our old Doulton brown jug across the road for a pint of milk. Elisa would serve me, her normally rather sad brown eyes twinkling brightly; one could almost hear her thinking, "I wonder if this little lad knows I first showed him the light o' day?" She was far too reticent to voice such a thought.

It wasn't unnatural to associate her with the old phrase "to hide one's light under a bushel". She probably held her erstwhile charges for a brief spell with the purest and most unrewarding love possible. It must have helped, in a very transient way, to fill this void in her otherwise mediocre existence. Elisa, your sweet soul deserves to rest in sublime serenity.

Page 2

Being born on an island, it was inevitable that the early years of my life would be closely connected with matters pertaining to the soil and the sea but this can wait awhile.

Most of us are usually interested in how our parents to "team-up"; particularly if they happened to come from different parts of the country. Distances had not yet been fore-shortened by the general use of the motor-cars and fast trains. There was a fair chance that one would marry someone from one's own locality, rather than otherwise.

Prior to his marriage, my father was running a reasonably successful business, which he had managed to build up

during a somewhat prolonged bachelor-hood. One facet of his business was hiring out horse-drawn vehicles. The use of

the internal combustion engine for road transport was in its early stages, though it was slowly creeping into general

use. Up to this time the horse-drawn carriage held the way angles to the driver, and appropriately are able to see

where they're going and where they've [been]. Dad owned a couple of four-wheeled carriages of the horse-following

type, which doubled for the occasional conveyances of clients to Colchester or its inconveniently sited railway

station (near a mile and a half to the north of town). He also had what was termed a wagonette, a four-wheeled

vehicle which was drawn by a pair of horses; so he had to maintain at least two serviceable animals at any given time.

This carriage was uncovered, longish, and "sprung' on all wheels, the hind pair being quite a bit larger than the

front. Presumably, because the greater circumference helped to "iron-out" the minor potholes in the roads. Though

this type of conveyance scarcely provided the most comfortable ride in the world, the local football and cricket teams were glade of it. There certainly wasn't much space available for "fans', as the maximum carrying capacity was for sixteen adults, plus a suitable corner for a 4 and1/2 gallon cask of ale. It says much for the coachbuilders of that time that the suspension was of the shackle-anchored leaf spring type, that, in its adapted form, is still in use on many of today's motor vehicles.

He also possessed what was known as a 'trap", a light, two wheeled vehicle which the French called "une charrette anglaise", which certainly sounds a bit more colourful. It was akin to the Irish jaunting-cart, a very practical type of conveyance, wherein the passenger's st at right been almost simultaneously. N dad's state of single blessedness, he had apparently laid the foundation of a successful business venture. But technical progress, my mother, myself and further additions were to change all that. Not that it was originally intended that his life pattern should unfold this way; that malevolently interfering old wrecker of man's best laid plans then took a crafty stir at father's particular portion of life's pudding. The new ingredient was my mother. Farther, with his obliging and quietly amiable disposition, had finally been persuaded that it was just about his turn to "polish the altar steps'. A distant cousin, appropriately named Georgina, was the intended partner in this venture.

George Smith senior

A bachelor, perched securely on the maternal roost, can usually devote much of his thought and effort to making a

little sound provisions for the future. But, knowing my father better than I've known any man, I've wondered long

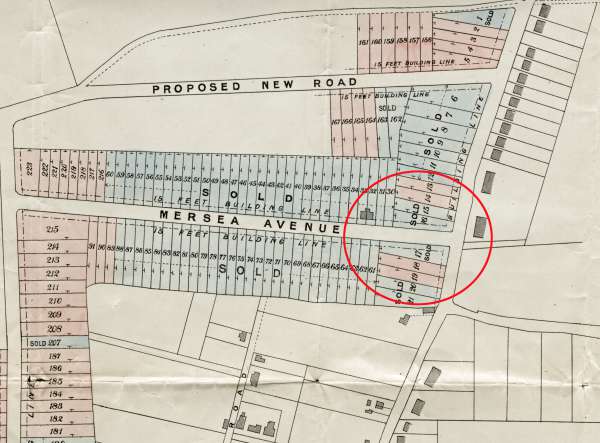

and deeply who prompted him to purchase a good plot of land on a very useful corner site [the corner of Mersea Avenue and High Street North]; and arrange to have a

fair-sized house built thereon. For beyond any shadow of doubt, it was the wisest thing he ever did in his whole life. Over the years, that house became

the life-raft that enabled us to sustain a modicum of dignity in often extremely adverse circumstances.

Page 3

The original cost of the plot was 50 pounds, and the house 200 pounds. His immediate outlay was 100 pounds, with

10 pounds on a 6% mortgage, which we always thought was a heavy percentage for those days. Come to think of it, the

old chap did quite a bit better than I did, for when I married (about twenty-six years later) I could only rustle up

just over 100 pounds, but in my case, that amount provided but modest furnishing for a small flat and a lethargic

week at Bournemouth.

After sixty years occupation by various members of the family, the old house was sold at several thousand percentage increase on the original cost, which certainly convinces me that there is definitely one investment that beats inflation in the long run.

Pardon my digression, but it seemed pertinent. The fact that a compact modern shop, now spanning the frontal width of

the house, still serves an ever expanding rural community, seems to indicate some foresight.

Plot 17 on the corner of Mersea Avenue and High Street North, bought by George Smith for £50 around 1904.

George senior's wife Edith opened a shop on this plot. She was known as Mrs 'Blucher' Smith because George always wore bluchers - a style of leather spat.

Entirely unaware that the ground-work for her future home was in progress, my mother was in good class service in a

socially desirable London Square, with Colonel and the Hon. Mrs. Weldon. Worth mentioning because she held this

kindly couple in high esteem. By reason of her personal outlook and upbringing she would have considered it beneath

her dignity to serve people for whom she had scanty respect. Besides, she was rather unusual that she had a definite

"superiority complex"; whether natural or required, I shall leave my reader to judge. She had been placed in domestic

work as an under-parlour-maid at the age of twelve, which was probably a lowly position at the bottom of the

pyramidal hierarchy of this form of service. She started with one advantage; no virtue of my grandmother's position

with a member of the Royal family she was assured of a place in a "desirable" household. Though one was merely a

servant, one at least had the satisfaction of serving under good conditions. For the real gentry would never have

thought of neglecting their staff any more than they would of neglecting their horses. Their whole mode of life was, in many ways, a miniature counterpart of that of today's Royalty. Very sensibly, they endeavoured to ensure that their employees were kept healthy, well fed and well-groomed. Not once did I hear my mother or grandmother complain that they had had to subsist on "the scraps that fell from the rich man's table. Most of us have had a

look around one or more of the stately homes of Britain, and overheard the hushed murmurs "oh, my dear, and the servants they had to keep!" Very true, and this numerous entourage was of mixed gender; one couldn't have the staff hopping in and out of each other's bedroom like some of the students at a modern university. Hence the need for fairly strict control, for the best employers felt that they had a certain moral responsibility, particularly with regard to the younger females. Besides, prolonged absences due to unwanted pregnancies disturbed the balance of the "service structure", When one had a sound, dependable retinue, it was reckoned to be well worth while to keep it intact. It must have been quite a problem in many of the country mansions, often many miles from anywhere. Human emotions have changed little down the centuries. One cannot cure a mouse liking cheese; one can but endeavour to keep the cheese in a safe place.

One result of living in a rather cloistered environment was that many eligible and good-looking young women had scant prospects of making suitable marriages. They just didn't have the opportunity of enough external social contact whereby they might find prospective matrimonial partners. At twenty-seven years of age, my mother was a fair example.

Page 4

It happened that she had become friendly with a very pleasant looking maid from an adjacent "town house". Emma

invited mother to the country for a weekend. "My older brother, George, will meet us at Colchester station with his

horse and trap", says she. He did, and was apparently swept off his feet at first sight. He probably proudly took her

to view the beginnings of his new house. Undoubtedly, this was his undoing, for if one is a personable bachelor with

tangible prospects of providing a respectable "nest', then a man needs to "gang warily'. Inevitably, he didn't.

Allowing for the fact that dad was an unworldly and unsophisticated countryman, he could not be blamed. Men have been

falling for wily female's charms since time began, and I very much doubt whether levels of intelligence have any

real bearing on this subject. The males, with a misbegotten sense of masculine superiority, delude themselves that

they do the "sorting-out". But when a woman really turns on the charm; as only a woman can; then a man hasn't a

chance! Dad certainly hadn't a chance!, neither had the unfortunate Georgina. Ever since I first learned of the

circumstances, I've had a very deep feeling of sympathy for this luckless maiden. It must have been deeply

humiliating, and one of the bitterest blows a young woman could suffer; more particularly in a small community.

Not that I ever met her, for she lived in a comparatively distant hamlet on the mainland. With the knowledge I now have, it would have been extremely embarrassing.

From the time I first began to think for myself, it used to puzzle my young mind as to why my mother didn't seem to

be fully accepted by my father's family. It's rather strange that a mere child should notice such things; and as I

grew older I assumed that it was perhaps because of her slightly "superior" air. Fortunately, it is far less

noticeable today, but up to a few decades ago it was customary for town and city dwellers to look upon people who

battled with the elements and worked very hard on the soil to produce food or them, as "yokels", "swede-gnawers" or

"clod-hoppers". Even the seeming polite term of "farm-labourer" did little to enhance the truth of their real

importance to the community. I was slightly incensed when I read this passage in a book, by a well-known authoress,

a few years ago; and mused deeply on the deviousness of some human thinking. She wrote, "I can't bear the

country ... I don't like ... all the trees and fields. The country's very nice if you like being next to nature, but

hate nature". Well, no-one denies her the right to have her likes and dislikes, for after all, this is common to

most of us. Then she ambles on, "Some people say what interesting faces country people have got; what thinkers they

must be. But I know what they're thinking bugger-all. Or nothing worth thinking about, like the crops, the farm

and is it going to rain, and looking up at the sky and musing about it. Of course it's going to rain. It always does

in the country ... And even if I don't know what they're thinking, I don't want to know".

It could be that the folk who produce her daily milk, and possibly her butter, cheese, bread, meat, fruit and

vegetables, were perhaps deep in thought wondering why they didn't seem quite so prosperous as many of their urban

visitors. Judging by the current cost of food-stuffs, I've a reasonable suspicion that they've begun (together with

their Continental collaborators) to realise their true economic value with relation to the rest of the community.

So it wasn't mother's slightly disdainful attitude towards country folk that put her into "semi-isolation" as far as

her in-laws were concerned. She knew the real reason, and no-one could have kept quieter about it.

Wedding of George Smith senior and Edith Head at Mortlake 28 December 1907.

Page 5

Father's family had no pretension as to lineage apparently, they had in the main descended from sound East Anglian

yeoman stock. With a surname like mine, it was slightly gratifying to know that my paternal grandmother bore the

maiden name of Beaumont, a not uncommon name in these parts. There's little doubt that some of the Conqueror's wondering warriors settled in the area.

Not that there's anything sacred about lineage, we all have it. It's fairly certain it would give many people

a pleasant surprise (or a shock) if they did but know the history of their forebears. It's just that some of us take

an interest and some don't. Incidentally, it's rather ironic that members of well known (their respective states) and

wealthy Australian families take great pride in the fact that they descend from the early convict-settlers. I believe

they have a right to be proud, for whatever the moral shortcomings of their ancestors, it took even something more

than "real guts" to carve a bearable life out of the primitive and inhospitable conditions that faced them. It's an

odd facet of the Briton's temperament that he always excels when he has his back to the wall in very adverse circumstances. In today's judicial "climate, many of the transportees would have received merely an admonition, an immediate couple of pounds out of the "poor box", and a regular income from the Ministry of Social Security.

Most families usually include one or two "characters" within their number, and we've had our fair share. Such a one was my paternal grandfather, a man of the farm-labouring class with personal ideas slightly above his children. He didn't take kindly to the idea the farmer should live in a large, comfortable house, and his employees in "poky" little thatched cottages. He had firm idea's about the "labourer being worthy of his hire". Fortunately, he was capable of operating and maintaining mechanical agricultural implements such as threshing machines. There were usually owned and "hired out" by the more prosperous farmers. It is worth recalling that it was opportune that the old man even found a mechanical thresher to operate, for a few years earlier the lowly soil-tillers of East Anglia had displayed unusual militancy in either burning or destroying many of "the new-fangled objects" on their original introduction. It was as understandable reaction, for none of us would relish the idea of even scanty means of livelihood being in danger of disappearing. Though this provided the local journalists with abundant "copy" for many

weeks, common sense ultimately prevailed.

Grandfather [Joseph Smith] had been persuaded to leave the Wivenhoe area with his numerous offspring's (nine, to be precise) on the

prospect of occupying an attractive and spacious old Georgian house [ Strood House ] at a rent of half-a-crown weekly. This was just

about balanced by the amount he received above the usual labourer's rate for his extra skill. Unfortunately,

contemporary land workers don't always receive the credit they should in these days of intensive, highly mechanized

farming.

It is with some pride that I pass the old house with its brilliant white cement-rendered walls. There it stands

on the edge of the Essex marshes, as secluded as anyone would wish, and yet an outstanding landmark from almost

every point of the compass. No wonder it sadly wounded the old man's pride when he had to leave it. But what could

one do on ten shillings a week old age pension? I believe the sub-cellar, where he regularly stored his 4 ½

gallon cask of ale, still exits. To the countrymen the beverage was both meat and drink.

Page 6

Such a man would make a hearty and appetising meal from a quart, a large hunk of home-made bread and some real

cheese. Seated under the leeward side of a hedge after a hard morning's work in the field, it used to taste

delicious; I know, I've tried it: The beer was cheap, very palatable, and nourishing; the product of a small, family

brewery. It had a slightly sweeter taste than modern brews, and I'm well aware it would be a sheer waste of time to

seek such drink today. When welcome visitors called, Grandfather would shout to grandma, "Emma fetch a jug of ale".

As head of the house, he would have considered it demeaning to say "please"!

Joseph and Emma Smith

The old man was tall, lean and austere, with slightly bowed shoulders, as became a man who had probably spent much

more of his life bending or stooping than standing upright. His leathery weathered beaten features were almost hidden by his neatly-trimmed Edwardian style beard. His piercing steel-blue eyes glinted under heavy greying eye-brows. A rather gruff, taciturn old man, who showed but scant interest in his grandchildren. After a brief "hello boys", he just behaved as though one was non-existent.

His only relaxation was an almost nightly visit to his favourite haunt, "The Rose", where I'm sure he did more

listening than talking; allowing himself the occasional terse, but non-committal comment. For him to disclose how

many hares, rabbits or wildfowl had had shot or snared that particular week would have constituted personal treason.

Among other things, I noticed that his household always seemed to be well supplied with fresh fish. Probably

exchanged for a suitable quantity of ale with one of his tavern cronies, thought I. It wasn't till I was a young man

that I learned the crafty old chap kept a primitive flat-bottomed boat hidden away in a small, adjacent creek.

He would paddle stealthily into the Pyefleet, a tidal tributary of the River Colne, preferably in the early hours or

at dusk, and set his equally primitive nets. He was steadfastly unrelenting in his efforts to ensnare that nature

should suitably supplement the household diet adequately. Seldom would he impart any of his nature lore to even his

own children. Any questions would be brushed aside with "A wise man never lets his right hand know what his left is

a-doin"! My father would occasionally seek plovers' eggs on the marshes and salting's in his younger days, and after

a really good search return with a mere two or three. The old man would grin knowingly, spit disdainfully in the

fire, saying 'I'll git ye some more in the mornin' Emma". Good as his word, he'd be up at daybreak, and by the time

the rest of the family rose there'd be a small bucket filled with Plovers' and Redshanks' eggs on the kitchen table.

As far as food scarcity was concerned, the First World War went past him almost unnoticed. His attitude was plainly, 'I didn't start it so what the hell has it got to do with me". He'd been buried too long to notice the second one.

Just after the Second World War, I happened to mention to a cousin of mine, who was like our grandfather in many respects that I fancied a feed of cockles. My home was in the "big city' at that time. I didn't fancy picking them up at the rate of one to every ten yards on the beach foreshore. "Ha".says he. "I'll take you up the creek to a

place 'grandfar' showed me". So at low tide off we went to a quiet part of the estuary where nought disturbed the

serenity of the afternoon but the cries of the sea-birds wheeling overhead. Apart from getting up to our knees in

"oozy" black mud. We had a couple of buckets filled in about ten minutes. One could almost scoop them up in

handfuls, plus a bit of gritty slush, of course.

Page 7

Knowing what I did, I couldn't resist asking Arthur how he came to wrest this "secret location" from the old man.

"Oh well, 'grandfer' never was very partial to cockles" he replied drily.

The mobile steam engine 'grandfer' operated was very much like George Stephenson's "North Star" locomotive of 1837 to look at, except that it had four wheels instead of six. Its power was transmitted to a he wheel at the side of its boiler, instead of its four heavily spoked iron wheels. Its traction was provided by the aid of a hefty pair of portable shafts, and a horse of the "Suffolk Punch" type. Under favourable ground conditions, an additional animal would be hitched on in front by means of a chain trace. As a child this squat-looking piece of machinery, with its huge flywheel and tail, "Rocket-type chimney, fascinated me. As the latter belched forth dense sordid smoke, it vibrated nosily on its broad wheels, suitably chocked with large wedge-shaped wooden blocks, which were a part of its accompanying impediments. The part that held my interest longest was the "governor", an odd-looking contraction consisting of two spherical iron balls suspended on two strips of metal from a rotating central spindle. This device ensured a uniform rhythm in the piston movement by regulating the admission of steam to the piston chamber. These balls whirled round at considerable speed when the old engine was going full blast; and though I knew nothing about the laws of gravity then, my youthful mind could not understand why they did not fly off into space. I hoped I'd be there when, through some mishap, they eventually did so, but was disappointed.

A few years later, when I was "assisting", at a "threshing" one of the farmhands, looking up at the "governor" turned to his mate, a rather wizened little man with a slightly hunched back, and said "Hey! Jess, oi reckon if you could do that, they'd turn you into steam injun" "if oi could do that oi recon oi'd join Barnum and Baileys" (an internationally famous American Circus), laconically replied he. Oh well, even a ribald laugh sometimes helps to relive the tedium of monotonous work.

A well preserved example of this comparatively simple but mobile, power supply, would today probably fetch more than

its original cost. Such are the quirks of human nature. There must be a childishly primitive streak in us that gives

a glow of pleasure to feel that we possess something that other folk do not.

I don't think the old man felt quite that way about his well-oiled double-barrelled shotgun. Apart from grandma, it was the most valuable asset he had, It was said that if he missed anything with his 'first barrel', he was morose for days. After all, he was an Essex man, and in the main there're as canny as Scotsman; and should you doubt this- try "beating" one in a deal.

I'm sure the old man must have turned in his grave with a grim chuckle when it was decided, no doubt after much cool and expensive military research, that troops operating in snow-clad areas should be camouflaged in white garments.

He had been doing just this since before 1900, when seeking hares under wintry conditions. He would let himself through the back door in his white over-garment, made-up of old sheeting by grandma.

Page 8

Wading grimly through the snow, he would find the fresh run of a hare that his knowledge told him would be feeding unsuspectingly down on the salting's whilst the tide was at low ebb. Then he would make himself as comfortable as possible on the sea wall, to await the return of his quarry. On his return he would examine his snares, and, if necessary, through the prevailing weather, re-set them.

Grandma would be industriously machining coats or trousers by the light of a Duplex paraffin lamp with its pleasing ruby-glass oil container. Thus she supplemented the family income by a few paltry shillings. The "made-up" garments were collected fortnightly by an agent of the local clothing factory, who left an appropriate quantity of "off-cuts: to occupy her spare time for another two weeks. Ill-disposed members of the family affirmed that it also helped to subsidise the old man's drinking habits. In those days the women-folk were not too prone to seek perfection in their husbands.

The old lady would be hoping he didn't return empty-handed (he seldom did), for it had the effect of making him as irritable as a bear with a sore head. The icy cold winds that cut mercilessly across the flat, open marshes, had the effect of making his eyes water badly. As he divested himself of his heavy poachers jacket, he would call "Emma, could ye let me 'ave a moiite o' rag to wipe my oiye out!". In his quaint way, he reckoned it was unhygienic to use his large multi-coloured handkerchief. If anyone remonstrated with him when he spat in the fire, he'd reply" abit be buggered". People weren't so germ-conscious then, but if you think on it, he certainly had a point. I, for one, am averse to carrying round a mucus-laden square of linen in my pocket, when afflicted with a cold.

Apart from the occasional gift of a pleasant, hare or rabbit to a relative, nothing was ever sold. For some odd

reason, it was against the old feller's principals. The latter were only slightly bent now and then when mine

hostess, a Mrs Bullen [ Pullen ], who presided firmly and efficiently at his favoured inn, would find wildfowl, fresh fish or a hare just inside her kitchen window. No words would pass over ancient oaken bar, finely polished by the passage of innumerable pints, regarding such mysterious discoverers; but gradfer would have a few pints of his favourite beverage "on the slate" that week, which the Mrs Bullen just as mysteriously erased on "settling day'. Such was the code of the country, for she respected the old man's skill and his secretive nature.

Within a year or two of my birth, the noisy automobile and motorcycle had begun to make their appearance, even or the poor roads of our seemingly remote areas. Cars, mainly chain-driven, by Bens, Packard, Daimler, Mercedes, Fiat, Peugot and Ford (in that order) had been produced prior to my "arrival". Names that have certainly stood the test of time. It gives one a mental jolt to realise that Henry Ford was mass-producing his world famous "Modal T" in 1908, when he made his first thousand. He averaged a million a year in the following twenty years. Long suffering humanity didn't stand a chance, for as my father often said "There's never a convenience, but that an inconvenience attends it"

Rural roads are not the clean, smooth-surfaced type we have long become accustomed to. Rough and very dusty in dry weather, they were remarkably akin to those I encountered in Iceland in 1941. According to the pitch of one's saddle, even a cycle ride could give one many a painful jolt in a vulnerable part of the male anatomy.

Page 9

Heaven knows what purgatory the earlier riders of the "velocipedes", the "bone-shakers", and the penny-farthing"

suffered.

Grandfer took no exception to the non-dust-raising cycles. The "mechanical monsters" he openly detested, and it was a matter for considerable family mirth that the old fellow used to hop through the hedge with considerable agility for a normally slow-moving man, and squat in the grass till the "stinkin; varmin" were all past, with the dust settled once more. There were two automobiles on the Island at this time, one of which was owned by the local vicar, the Revd. Pierrepoint Edwards, and staunch patriot if ever there was one. He later became chaplain in the 54th Division in World War one, where he was appropriately decorated with the Military Cross for "Assisting in the rescue of badly wounded men under heavy enemy shellfire". he was also reported to have felled a drunken man with a single well aimed right hook, when the latter had temerity to insult his "calling. Consequently, it was by no means strange that he became widely known as the "Fighting Parson". He was purely by chance that I later discovered that both he and his rather prim wife came from "crested families".

One moonless night, whilst the old man was making his customary half-mile trek home from the inn, he suddenly became aware of the "spit, fart and bang" of the vicar's "De Dion Bouton" behind him. He went to take his usual spring across the adjacent ditch, but the a moite improbable effects of an extra pint or so seemed to have affected the efficiency of his natural "radar", for he caught his foot in a thick, trailing bramble, and fell face first into the muddy dike. We could well imagine his hasty, scrambling exit from the wire, and his standing at the edge of the road, frenziedly shaking his horny fist and calling down curses of hell upon the crimson-hued dispenser of the holy message, suitably phrased as to the possibility of dubious parentage. Grandfer duly arrived home, dripping evil-smelling water, and still wearing his greasy old wide-brimmed felt hat, that looked like one that had "be caped" from the Australian outback at some period of its long life. He paused just inside the door, then shouted "Emma, have ye got a moite o' rag" ...

After she had fussed over him awhile, and he'd regained his calm, he looked her sternly, saying "Don't you ever let that lible-bred ale tub-thumper say the last roites over me, They lot ha' bin roidin' on the backs o' the worker far far too long!" As one might well expect, the old cleric eventfully did have the "last words" as far as Grandfer was concerned. But the latter would have been gratified to have that, at least, their bones don't moulder in the same cemetery.

Grandma [Emma] was a quietly spoken little woman, grey-haired, with a nature as sweet as her lined face, and as

fragile-looking as the cupids on a delicate piece of Dresden china. The perfect partner for a man such as

grandfather. Few women can have had much less of the material things that are usually dear to the female heart.

She was devoted to the old man several years after, when he has gone, she remarked sadly, "It's four years today

since we buried your Grandfather" As the tears dimmed her pale blue eyes. I said, don't worry, grandma, we'll all take care of you. "I know that", she replied, and with heart-touching hint of a terrible loneliness in her voice, "I's really only waiting to join my Joe". Knowing that most of the family thought of him as a gruff, crotchety, and irritating old man, it dawned on me that she had "summered and wintered" with him through what would now be considered very hard times; she knew full well of the good in him. To me it was a chastening and beautiful thought that though his family

(and many others) had a certain respect for him, she was probably the only person in the world who really loved him.

Read More

Chapter 2

|