| Abstract | FOREWORD

Original online transcription by Geoffrey Russell-Grant May 2002

Geoff's forword:

IMPORTANT NOTE: Mary Hopkirk's 'Story of Layer de la Haye' was written in 1934 and has been out of print for many years.

As there is little or no prospect of it being re-printed it is being made available on the internet, free of charge, for the

purposes of private study and research only. Anyone considering reproducing it in any form, either directly or indirectly,

for any commercial purpose should first make appropriate enquiries about copyright.

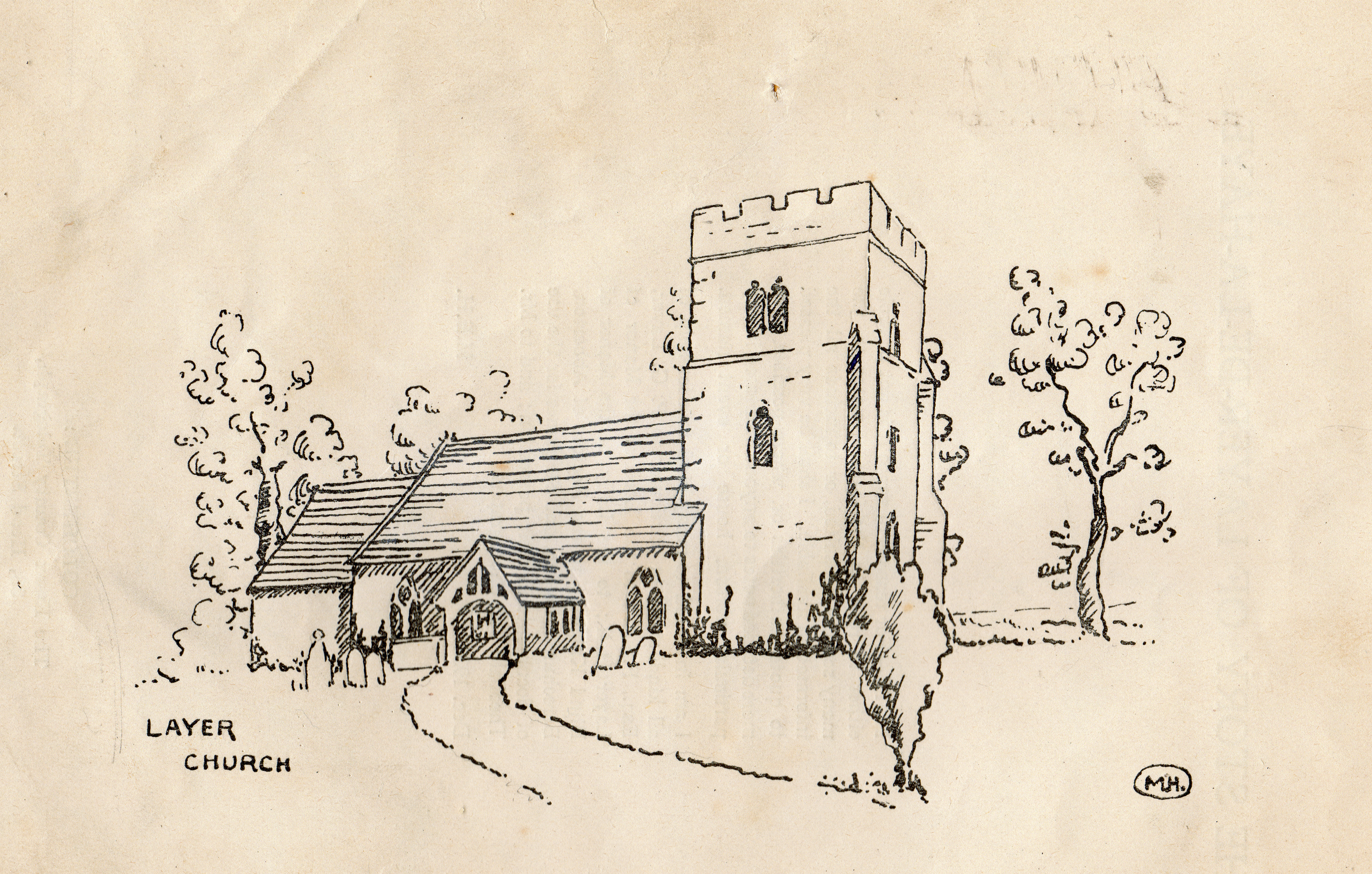

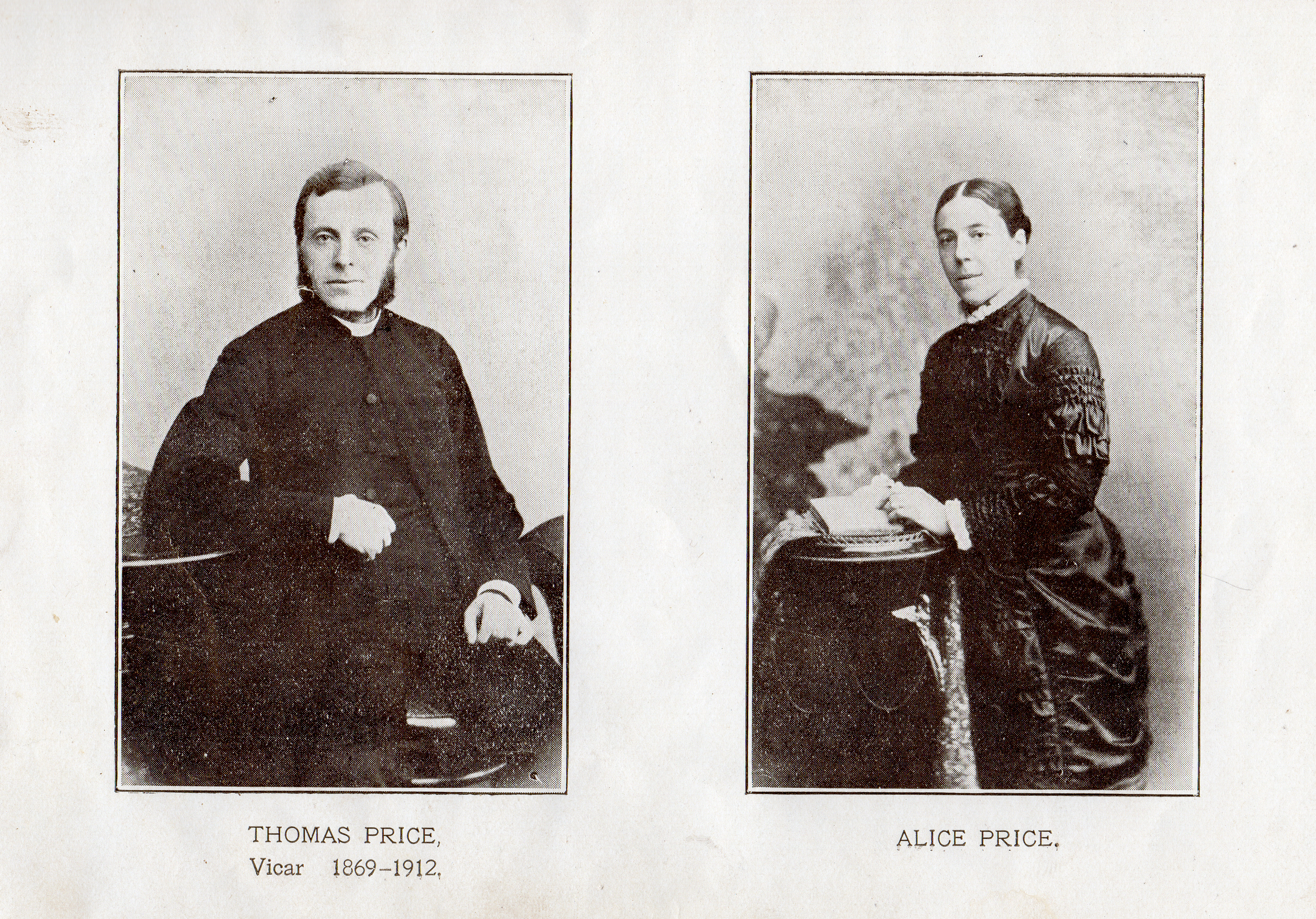

This document contains only the text of the booklet. The original booklet contains pen and ink drawings of the church and some old Layer de la Haye houses by Mary Hopkirk, a pen and ink drawing of Layer Mill by P Mackay, and photographs of the Revd John Dewhurst, his wife Elizabeth, the Revd Thomas Price, and his wife Alice.

Some notes have been added, in italics, giving relevant new information which has become available and referring to changes which have taken place since the history was written. These are not, nor intended to be, comprehensive.

Updated version March 2024 by Tony Millatt.

Added original illustrations from a copy of the book which has come to light in some Millatt Family papers.

THE STORY OF LAYER-DE-LA-HAYE.

By Mary Hopkirk, M.A.

NOTE - For reasons of space it is not possible either to refer in the form of notes to the many sources consulted, or to include all the information available. I shall be very pleased to quote authorities or, where possible, give more detailed notes to anyone interested in any particular person, house or event named.

I am indebted to many kind folk for help of all kinds; and in particular to P. G. Laver, Esq., F.S.A.; to the Lord of the Manor of Layer Hall; to the Lady of the Manor of Blind Knights; to the Rectors of Abberton, Berechurch, Peldon, and St. James for the use of documents in their possession; and to Mr. Theobald for photographs.

Dec. 1934. M.E.H.

COLCHESTER:

The Essex County Telegraph,

38, Head Street.

THE STORY OF LAYER-DE-LA-HAYE

For most people history begins in 1066; but many things happened in Layer-de-la-Haye before that. There is evidence of the presence of primitive man at Fingringhoe, who, although he left few traces in Layer, must often have pushed his way through the great forest bordering the Roman River to hunt for his dinner in Chestwood. This, however, is mere conjecture. . . .

But the Romans left their mark. A road, part of their elaborate defences round Colchester, crossed Chestwood and terminated at the corner of the Vicarage meadow, where it connected with a peculiarly wide ditch. This road is still traceable, and it may be assumed with confidence that Roman legionaries strolled about in what is now the Vicarage garden nearly two thousand years ago.

A thousand years then elapsed, of which little is known save that Vikings and other pirates hung about the marshes, and fought a great battle at Wigborough, doubtless visiting Layer from time to time and taking away anything worth taking.

THE ELEVENTH CENTURY.

There are two explanations of the name Layer given by the English Place Name Society, the second of which, a Scandinavian word Leire meaning clay, seems the more likely in view of the nature of the soil in the vicinity of the Layer Brook which flows through the three Layer villages.

At the time of the Norman Conquest, Layer, then called Legra, belonged to a Saxon freedman named Alric, who had cleared 330 acres. The rest of the parish, now 2,577 acres, was heath and marshland. His equipment consisted of: 1½ plough teams, 1 unfree tenant, 2 serfs, 3 beasts, 38 sheep and woodland for 40 swine; and the value of the estate was £4.

William the Conqueror gave Alric's manor to a Norman, Eustace, Earl of Boulogne; and by 1086 it had decreased in value to £3. Eustace employed four men instead of three, and had 2 plough-teams, 5 cows and 146 sheep. He added 6 hives of bees, and built a mill, almost certainly on the site of the existing one, where his tenants were obliged to grind their corn and pay him for the privilege of so doing. Through the marriage of his granddaughter Maud to King Stephen, Layer afterwards became Crown property.

THE TWELFTH CENTURY.

THE Earls of Boulogne did not, of course, live on their Layer estate themselves, but had a series of tenants and sub-tenants who paid rent in money or military service. The first recorded tenant is named in a charter of 1128, which states that the Benedictine Abbey of St. John in Colchester owned the Church of Hea and two-thirds of the tithe of Legra, the demesne of Walter de la Haye. Although the lord of the manor was obliged to pay one-third of his tithe to his parish church, it was his privilege to pay the remaining two-thirds to the religious establishment of his choice; and this is clearly what had happened in Layer.

Of Walter de la Haye little is known. A family of that name came from La Haye du Puits, near Coûtances, with the Conqueror's army and prospered greatly in England; but it has no recorded connection with the family which gave Layer the second part of its name. If the De la Hayes of Layer did not hail from La Haye du Puits they may perhaps have come from Val de la Haye, near Rouen, where there was an establishment of Knight Templars; and there may conceivably be some link between this supposition and the origin of the name Blind Knights.

The De la Hayes of Layer were generous benefactors to St. John's Abbey, of which Hugh de la Haye was Abbot from 1130-1147. In addition to the tithe already given by Walter, Maurice gave 60 acres of land, and Athelais, wife of Ralph, gave another eighty. Maurice's gift was approved by his overlord, a certain Hugh, son of Stephen, who was also feoffee to the Crown.

A charter given by Richard I in 1189 discloses the fact that in addition to some land, the Augustinian Priory of St. Botolph held "the Church of Legra and all its emoluments" (presumably the remaining third of the tithe), and supplied the clergy. This seems to contradict the fact that the Church of Hea had belonged to St. John's Abbey in 1128. Either it changed hands during the intervening years, or there were two churches, one of Legra and one of Hea. In neither charter, nor indeed in any known document, has the dedication of the church been found. Architecturally, the older portions date from this century, and the builders incorporated some Roman brick in the south-west corner of the chancel, where it can be seen to this day. Perhaps they pillaged some Roman buildings in the vicinity.

THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY.

MANOR OF LAYER-DE-LA-HAYE.

About 1240 the lord of the manor was Ralph de la Haye. The overlordship was still vested in the Crown, but he held other land in Layer from the Earl of Ferrers and Henry de Essex, amounting in all to 366 acres. After considerable litigation with the latter about the rent, Ralph was fined for not paying it, and, dying in 1253, was succeeded by William de Munchensi, the younger son of a well-known Suffolk landowner, holding estates at Edwardstone. How he became heir to the De la Hayes is not known, but the manor was immediately claimed by Ralph's widow, Lucia, as her jointure, "wherewith her husband had endowered her when he espoused her at the church door." She won her suit and kept the manor for life, with reversion to William de Munchensi. William died in 1283, and his son and heir, also William, being imprisoned for trespass, forfeited his lands to Queen Eleanor. In 1291, however, she restored them on condition that he joined the Last Crusade.

Meanwhile there had been changes in the overlordship of this domain. The manor itself still belonged to the Crown; but the other holdings changed hands. In 1267 Henry III confiscated Earl Ferrers' estates, giving them to his own son, Edmund of Lancaster; and Hugh de Essex granted his land in Layer to Sir Philip Bassett, from whom it passed to his daughter Alice, Countess of Norfolk. After a lawsuit with her widowed stepmother, who claimed one-third of the Manor of Leyre sur Laye as her jointure, Alice died in 1281, leaving 144 acres in Layer, valued at 58s. 6d. yearly, to her son by a former marriage, Hugh Despencer.

MANOR OF RYE.

In 1289 a certain John, son and heir of Adam de Ry, added 166 acres to the land already owned by St. John's Abbey, stating that this was all he owned in Layer. He gave his surname to what was always afterwards known as the Manor of Rye. The Priory of St. Botolph had been John de Ry's tenant, and continued to pay rent for this land to the Benedictines. The Prior also seems to have owned some land to the south-east of the Rye, for soon after John de Ry's gift there was some disagreement between the two monasteries about a certain road which ran through the courtyard of the Rye Manor across Hawysesbregge to Wigborough. It was finally agreed that the Prior of St. Botolph and certain Wigborough notabilities would relinquish their right to use this road in exchange for the use of another offered by St. John's to the westward. The Augustinians continued to own the emoluments of the church, which in 1242 were worth £7 yearly.

At the end of the thirteenth century therefore St. John's Abbey was the second largest landowner in the parish with about 300 acres. William de Munchensi came first with about 366, which he held in three portions from the King, Hugh Despencer and Edmund of Lancaster respectively. Other landowners were William Clarke with 40 acres, St. Botolph's Priory, St. Osyth's Abbey and the Moleshams of Wigborough.

By 1299 someone had built a bridge at Kingsford.

THE FOURTEENTH CENTURY.

MANOR OF LAYER-DE-LA-HAYE.

William de Munchensi died in 1302, perhaps on his return from Acre, and in 1317 his son, also William, sublet the manor to a certain Hugh de Nanton and Eleanor his wife. Two years later William died also, leaving a baby of three to succeed him. In 1325 two priests, probably the boy's guardians, re-granted it to Hugh de Nanton.

In 1327 there was another change in the overlordship of part of little William's estate. Hugh Despencer was beheaded by Edward III for rebellion, and his lands forfeited to Edmund, Earl of Kent, the King's uncle. Three years later Edmund's own turn came for decapitation, but his two little boys, Edmund, who died in 1333, and John, were allowed to inherit his Earldom and his property.

Then came the Black Death. This epidemic, a kind of bubonic plague, had an effect on village life that cannot be over-estimated. So many people were wiped out that the feudal system began to break down. The surviving landowners, unable to find enough labour, found it more profitable to let their land in small holdings to sub-tenants than to attempt to farm their large manors themselves, and the yeoman farmer dates from this century.

The plague took John, Earl of Kent, and the overlordship of the Manor of Layer-de-la-Haye was thenceforward vested wholly in the Crown. The Munchensis seem to have been smitten also, for they disappear from the annals of the village about this time. Nor did their tenants fare any better. Hugh de Nanton, John his son, and Edmund his grandson all died before 1353; and in the following year the tenant was Walter Baynard.

Thirty years later a certain John Codlyng, parson of Stratford, Suffolk, let the manor to Sir John de Sutton, Sir Richard de Sutton, John Boys and John Battaille. Whether these people, who were related and were perhaps the trustees of some child, had any connection with either the Munchensis or the Nantons is not clear.

1. Bears and Marthas, 2. Blind Knights, 3. Mustow House, 4. Heath House, 5. Wakelins, 6. Spicers.

MANOR OF RYE.

Meanwhile the Benedictines were slowly enlarging their manor of the Rye. In 1305 Edward I licensed William, the son of Isolde, to give them 18 acres; and John Savare gave 14, "a bit of land lying below the Abbot's garden." In 1365 the Abbey received yet more land, this time from Peter Wavaye (probably Harvey) and John Chaterys for the repose of their souls.

MANOR OF BLIND KNIGHTS AND THE CHURCH.

The Augustinians did not do so badly either. In 1352 Edward III licensed them to acquire a messuage and 108 acres of land from Nicholas de Sutton, parson of Great Wigborough, valued at 43s. 10d. This land was the Manor of Blind Knights, and a Norman arch recently uncovered in the manor house suggests the existence of a building on this site at an early date. In 1364, after a sanguinary quarrel with the rival monastery, St. Botolph's agreed to exchange its tithe for that of the Rye, and built the existing tithe barn for the extra sheaves. In 1399 Richard II licensed Thomas Whot and John Hervy to give the Prior 28 acres. John is the first recorded member of a family which gave its name to Harvey's Farm, and which was to own land in Layer for the next 500 years.

These Royal licences were the consequence of the Statute of Mortmain. Edward I, realizing the danger of the increasing wealth of the Church, tried to hinder further gifts, by insisting that the King's permission be obtained first.

Nevertheless the Priory seems to have taken its added responsibilities seriously. Immediately after the Black Death the monks began restoring the neglected church, re-building the nave, the tower and the north porch. The stone probably came from Caen in Normandy, whence it was imported at this time in considerable quantities.

One wonders which bit of Layer was the subject of the following romantic litigation:

In 1326 one Oliver de Blonville went to law with Joan, the widow of Simon de Segrave, about some land in Layer. The dispute was settled by his undertaking to give her one rose on the Nativity of St. John Baptist yearly. Shortly after this Oliver went to law again, this time with Joan his wife against John Sayer (the John Savare who had given land to the Abbey) and Nicholas Hacoun about the same property, which John agreed should revert eventually to Nicholas de Segrave, Joan's son by her former marriage.

Other Layer notabilities of this century were the Nevards, who owned land in Layer-de-Ia-Haye and Layer Breton, almost certainly the existing farm of that name; Robert, parson of Great Wigborough; Walter de Pateshill, who owned property near the Wigborough border; and John Eylot, who was admitted a burgess of Colchester in 1395. A less respectable inhabitant was Robert of Layer and Joan his wife, who were fined four times in four years for selling beer contrary to the regulations.

Layer Mill (upstream) by P. McKay.

THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY.

MANOR OF LAYER-DE-LA-HAYE.

The manor next belonged to Sir Robert Tey, who may have inherited it through his wife Anne, widow of a John Nanton, or through an ancestress, Emma, who was also a Nanton, but strangely enough used the De la Haye coat of arms.

The Teys were a family of considerable standing locally. By a series of advantageous marriages during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries they had acquired large estates in Aldham, Birch, Copford, Peldon, Layer and the three villages to which they gave their name.

In 1426 Sir Robert Tey was succeeded first by his grandson and then in 1441 by his great grandson, both named John. The latter

lived during the Wars of the Roses, and was one of the gentlemen of Essex ordered by Henry VI to resist Warwick the Kingmaker.

John's policy, however, was "not to be hanged for talking," and he placed his motto Tais en Temps beneath his coat of arms in the windows of his house. This manor house, which was "large and fair," stood opposite the church on the site now occupied by the Hall, for at least three centuries. John was succeeded in 1462 at Layer (but not elsewhere) by his brother Robert, who died twelve years later, leaving the manor to his son William, a boy of twelve.

MANOR OF RYE.

At the end of the century the Benedictines built the house now called the Great House on their manor.

MANOR OF BLIND KNIGHTS AND THE CHURCH.

St. Botolph's, not to be outdone, rebuilt the house of Blind Knights, incorporating part of the earlier structure. In addition to their landed property, which was definitely described to the Bishop in 1406 as a manor, the monks continued to hold the tithe and advowson of the church. In this century they re-built the chancel arch and gave the bell frame and the fourth and oldest existing bell. This was cast about 1459 by a woman, Joanna Sturdy. Her husband, a well-known bell-founder of Sudbury (John and Johanna Sturdy were bellfounders at London, not Sudbury. Perhaps there has been some confusion with the founder of another of the bells, Thomas Gardiner, who was at Sudbury), had died in 1458, and she fulfilled the remaining orders before retiring from business. The bell bears the inscription: In Multis Annis Resonet Campana Johannis (May John's bell ring through many years). The founder's pious hope has certainly been fulfilled, for her bell still rings.

In 1495 the Prior appointed the first recorded incumbent of Layer, Ralph Richardson.

The fifteenth century saw Layer's first and only (recorded) crime: Thomas Lymenour, a debtor, had taken sanctuary in St. John's Abbey Church. On the Feast of St. Bartholomew 1413 he left the Abbey, broke into Layer de la Haye Church, and stole a missal worth £7 13s. 4d. Returning with it to the Abbey he was caught by a monk, who handed him over via the Abbot to justice. In view of the lack of cordiality obtaining between the monasteries, one cannot help wondering whether the Benedictine Abbot's horror with regard to this episode was as great as might be expected. Thomas was fined 40s., but what became of the missal is not stated.

THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY.

THE MANOR OF LAYER-DE-LA-HAYE.

William Tey died in 1502, and his son Thomas succeeded to the manor, then worth £25, and which included Nevards and William-a-Birches, now a ruined house by the lake to the west of the Hall. Thomas and his wife, Jane Harleston, saw the power of the monasteries completely destroyed, and the Rye and Blind Knights in secular hands. He died in 1543, and was buried in a grey marble tomb on the north side of the chancel. This had two brass effigies and bore the inscription: "Of your charité pray for the soules of Thomas Tey, Esquire, sometime of this town of Layer, and Jane, his wife, on who soules and all christen, Jeshue have mercy." The effigies and inscription had disappeared two hundred years later, but the tomb remains, and is called erroneously "The De la Haye Tomb."

There were other memorials to the Teys on the south wall of the nave, which disappeared with the wall in the nineteenth century. One was to a man called "Standing Tey," who, on the occasion of a duel, vowed that if he lost "he would never eat his meat but standing." The inscription did not state how the duel terminated.

Although Thomas Tey's son and heir, John, managed to steer safely through the persecutions of four Tudor Sovereigns, he saw an even greater religious upheaval than his father had seen, and dying in 1568 left two sons, the elder of whom, Thomas, inherited the estate, and the younger, William, became vicar of Layer in the following year.

In 1571 Thomas Tey let the manor to his cousin, Sir Robert Drury, retaining only Chestwood, Perryfield and Parkfield, which are still so named to this day. In 1594 Norden passed through Layer and saw the Tey arms in the windows of the Manor House; but two years later Thomas Tey, who seems to have come down in the world, sold it to Peter Bettenson, of Foxton, Staffordshire, whose heirs owned Layer Hall for the next hundred years.

MANORS OF RYE AND BLIND KNIGHTS.

In the meantime Sir Thomas Audeley, Lord Chancellor of England, took advantage of the suppression of the monasteries by Henry VIII in 1536 to appropriate Blind Knights and the Rye, together with the Mill, the tithe and advowson of Layer and certain small holdings called Harveys, Wards, Giles and Heathouse. He had also taken Berechurch and Abberton; and from thenceforward for nearly four hundred years all the former monastic property in Layer formed part of the Berechurch Hall Estate.

Audeley did not live long to enjoy his ill-gotten gains. He died in 1544, and like many other sacrilegious persons, cursed by the monks, he left no direct male heir. The Layer part of his estate passed to his nephew Thomas, who died in 1572, possessed of Blind Knights, the Rye and about 60 acres adjoining, called Harveys, Wards, Giles, Heathouse, Holts, Savares, Symmes, Bealdes, Graftons, Underwoods, Glevers, Cleves, Layer Mill and the tithe and advowson. His tenants were John Lucas, George Foster, George Christmas, esquires, and Arthur Clark, gent. Thomas Audeley's widow, Katharine, "a bold and turbulent woman," tried to withdraw her jointure in Berechurch out of the bounds of the Colchester Corporation, but, after a long contest, gave in. She owned land in Layer called Rosses, "let to her servant Anthony Ash," and died in 1611. Her tomb at Morton-on-the-Hill, Norfolk, states that: "She lived forty-five years a widdow. She kept good hospitality. She was charitable to the poor."

The next heir was Thomas Audeley's son, Robert. He does not seem to have lived on his estate, but his uncle lived at Gosbecks, and was buried at Berechurch at the end of the century, leaving several children. One of these, John, had bought Nevards from the Teys, and left £10 annually from it to a nephew. His tenant there was Henry Addams, of Abberton Hall. Another of Thomas' children, Francis, was the father of the Rev. John Audeley, who was later to become incumbent of Layer.

THE CHURCH.

Only four sixteenth-century incumbents are recorded. A certain Sir Roger Church was parish priest in 1510, and may have been the last pre-Reformation incumbent. He was described as "an active man," and may have been a Grey Friar. In any case he championed the cause of the Franciscans in the reign of Henry VII, and became their Prior when they were re-instated.

About 1567 Thomas Audeley presented Stephen Caterall, who had previously been curate of Kirby-le-Soken.

He was succeeded in 1569 by William Tey, M.A., brother of the last lord of the manor of that name. Born at Layer in 1546 and educated at Trinity College, Cambridge, he was ordained by the Bishop of London, and became incumbent of Layer and Peldon at the age of 23. He seems to have had Presbyterian leanings, for he was a member of the Dedham Classis. In 1588 he and his Layer churchwardens were reprimanded by a Court held at Colchester, which found "Ye Register Boke ys not orderly kept for that there ys but one lock and ys kept locked with one key which key ys kept by ye sexton contrary to Hir Majesty's injunctions." The churchwarden, Anthony Bracket, who appeared, was directed to see "that ye Register Boke be kept and that ye former chest hath ii new locks and ii. keys, ye minister to have one." This irregularity may have been due to the fact that William Tey also had Peldon to look after, and probably lived there. Perhaps he gave the beautiful Elizabethan chalice and cover-paten which are used in Layer Church to this day. Tey held both livings till his death in 1595, and was succeeded by Roger Goodwin.

In 1511 Richard Duke left money for the purchase of land for the church. He gave his name to a farm called Dukes, on the site of the Layer Poultry Farm, and probably lived there. There were also other endowments: "Given out of the land called Furchers in the tenue of Robert Scarlett to find a lamp light before the Trinity, 8d.;" "Out of Garlands in the hands of John Smyth and Robert Field to find two pounds of wax for the rood light for ever, yearly 8d." Garlands is not the farm of that name in Birch, but that which is now called the Great House. "Ever" proved to be of short duration, for between 1730 and 1769 all trace of these benefactions had disappeared.

Other sixteenth century notabilities were Richard Harvey, who became a burgess of Colchester in 1503; John Chambre, a yeoman; and the miller, Henry Salmon, who, dying in 1601, left 2s. to his daughter Margery Bundocke, and 3s. 4d. to his sons-in-law, Thomas and Anthony Harvey and Thomas Wood. He left the residue of his estate to his wife Ann.

Early in the century somebody built the cottage standing alone on the hillside to the south west of Kingsford Bridge; and by 1563 the Roman River was bridged at Brownsford (now Bounsted).

Thus at the death of Queen Elizabeth the two chief landowners in the parish were Peter Bettenson, of Layer Hall, and Robert Audeley, of Berechurch.

THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY.

THE MANOR OF LAYER-DE-LA-HAYE.

Early in the century Peter Bettenson died, leaving Layer Hall to his brother Richard, who lived at Scadbury, Kent, and at Eagle House, Wimbledon. In 1624 he was succeeded by his son, also Richard, who owned it for half-a-century, and seems to have been a Royalist during the Civil War, for although he either left the country or lay very low, he was made a Baronet by Charles II in 1666 presumably for services to the Royal cause. He bought back Nevards from John Audeley's heirs, and in 1656 settled his Layer property on his wife Anne. In 1675 the Hall was let to a certain Joseph Baker, the first recorded member of an old Layer family. Sir Richard's eldest son died in 1677 at Montpelier in France, leaving a boy of eight, Edward, to inherit his grandfather's baronetcy and mortgaged estate in 1679.

BERECHURCH HALL ESTATE.

Robert Audeley died in 1624, leaving, in Layer, Blind Knights, Reves, the water mill, tithe and advowson to his son, Sir Henry, who had been knighted by James I two years previously. The widowed Mrs. Audeley, however, held part of the Layer estate for her life, and paid Ship Money for it in 1636. In the same year Sir Henry, who was her stepson, summoned her for having felled six hundred cartloads of timber "to the great damage of her estate." He had settled the reversion of his stepmother's jointure on his own wife, Ann Packington, some years earlier.

Mrs. Audeley died in 1641, and Lady Audeley only survived her for two years, leaving a feeble-minded son, Thomas, and two daughters. Her jointure, consisting of Blind Knights, the Rye, Reveshall, Graftons, and the tithe and advowson of Layer, together with Badcocks at Abberton, should then rightly have passed to her children, but owing to the upheavals incidental to the Civil War nothing definite was settled.

Sir Henry, who was a Royalist and a "Roman Catholic conforming to the Church of England," fled to France. In his absence the Parliamentary Army cut down 300 oak trees on the Berechurch estate. About the same time "an insurrection of the common rude people took place, and, believing him to be a Roman Catholic, they defaced and despoiled his dwelling-house called Berechurch." After having to pay £1,600 for the return of his estates, he returned to England in 1645, where he seems to have lived quietly, for nothing more is recorded of him until 1664, when his death, perhaps of the Great Plague, precipitated a family quarrel. He had married secondly Anne Daniel, by whom he had two sons. This lady was accused by her stepdaughters of having persuaded Sir Henry to alienate his first wife's jointure, which rightly belonged to them and their lunatic brother. Whether Anne was to blame or not is not clear; but certain it is that, whereas poor Thomas was certified in 1663, and Sir Henry placed the tithe of Layer for his maintenance, he seems to have made no attempt to transfer the remainder of Anne Packington's jointure to her daughters. In fact, he left his Layer estate to his third son, Francis, with reversion to the second son Henry, who inherited Berechurch.

When Francis died in 1681 the quarrel re-opened. The elder sister, Katharine, wife of Mr. Barker, of Monkwick, managed to secure Abberton and the advowson of Layer for her own daughter Appolonia upon her marriage to Francis Canning, of Foxcote. But Henry Audeley seized all the Layer land, and, upon the death of mad Thomas in 1687, took the tithe also. In 1693 he went to law with Sir Edward Bettenson, who very properly objected to his describing Blind Knights as the Manor of Layer-de-la-Haye.

THE CHURCH.

During the century there were changes of some importance among the Layer incumbents, all of whom were Cambridge men.

About 1612 Roger Goodwin gave place to John Harris, B.A., of Christ's College, and in 1627 John Parker, M.A., of Queen's, a Londoner, was appointed by Sir Henry Audeley but resigned within a year to become Rector of Westerfield.

Of Suffolk yeoman stock, his successor, Thomas Partridge, M.A., of Emmanuel, was ordained in 1627 at King's Lynn, and was appointed to Layer in the following year at the age of twenty-five. Two years later he died, leaving a widow and an infant son, and is presumably buried in the churchyard. His will, leaving all his "goodes and chattels" to his wife Elizabeth, was witnessed by three Layer people, Thimble and Mary Westbroom and Alexander Digby. Thimble owned land in Layer in 1636, for which he paid Ship Money. Alexander Digby was probably the only other person in Layer who could write. He, too, was a landowner, and his sons were with Westbroom's boy at the Colchester Grammar School.

Partridge was succeeded by a Layer Breton man, John Argor M.A., of Queen's, who was presented by Sir Henry Audeley in 1632 at the age of 30. He left Layer-de-la-Haye in 1639 to become Rector of Leigh, and, becoming a Presbyterian, was appointed to Braintree under the Protectorate. After the passing of the Act of Uniformity in 1662 he refused to conform to the Established Church, and was ejected from his benefice. He continued, however, to live in Braintree as a teacher in the parish school, and his parishioners who considered him "well approved for learning and doctrine and an able preaching minister," gave him £100 as a token of esteem. Owing to the Five Mile Act forbidding ejected ministers to live within five miles of their former cures, he moved to Copford, and was subsequently licensed to preach at Copford Hall, the house of Hezekiah Haynes and at that of Zachary Damon (Damyon or Demmant) in Birch, which were "places of meeting of the Presbyterian way." Haynes had been one of Cromwell's generals and Damon was his tenant. When John Argor died in 1679 at the age of 77 a friend wrote:

"He was a very lovely Christian. . . . When his livelihood was taken from him he lived comfortably by faith. Being asked how he thought he should live, having a great family of children, his answer was, as long as his God was his housekeeper he believed he would provide for him and his."

He kept a diary of God's providences towards him of which the following entry is typical: "January 2nd, 1663. I received £5 2s. 0d. This was when I was laid aside, so graciously did the Lord provide for his unworthy servant."

John Argor was succeeded at Layer by a High Churchman, John Audeley, M.A., of Christ's. In 1640 his cousin, Sir Henry Audeley, presented him to Layer, but he was ejected in 1646 when Presbyterianism was established in England. In 1648 it was reported that there was "no minister;" yet the Audeleys still regarded him as the incumbent, for in 1650 and again in 1653 it was reported to Cromwell's commissioners that the minister was "Mr. John Audeley, forced upon them by Sir Henry Audeley." The position probably was that the Anglicans considered him the rightful incumbent while the Presbyterians did not. The living was then worth £20.

With the return of the Stuarts the conforming clergy were quietly restored to their benefices, but John must have left or died meanwhile, for in 1661 Sir Henry Audeley appointed Thomas Parker curate of Layer and Berechurch. He evidently conformed, too, for despite the Act of Uniformity, he retained his cure, then worth £60, until his death in 1698. His beautiful handwriting may still be seen at Berechurch, but his Layer registers, though still extant in 1830, have since disappeared.

His successor in both parishes was Richard Reynolds, a grandson of Richard Reynolds, rector of Abberton. He graduated from Sidney Sussex College in 1672, and was a protegé of the Bishop of London, on whose recommendation he was elected Headmaster of Colchester Grammar School in 1691. This post he held until 1702, and was described as "a good and diligent master." It is uncertain who presented him to Layer in 1698. The rightful patron was Francis Canning, the husband of Sir Henry Audeley's granddaughter Appolonia Barker; but as a Roman Catholic who afterwards became a non-juror, i.e., one of those who refused to take the oath to George I in 1715, it is doubtful whether he was allowed to exercise his patronage.

Among the inhabitants of Layer at this time was a certain Thomas Ball, who paid ship money in 1636, and gave his name to Ball's Lane, where he probably lived and built the early seventeenth-century house called Ardley's. He was elder of the church in 1646 (then Presbyterian), and it was doubtless he who reported to Cromwell's commissioners on the Rev. John Audeley. He was evidently a person of some importance, as the documents relating to him consistently describe him as "gent." His fellow elder was Mr. Strange Chapman, a freeholder. Other Layer notabilities living at this time were Richard Duke, who had probably succeeded his grandfather at Dukes Farm, John Clarke, William King and Thomas Reeve, gent., who was a freeholder in 1694.

In 1682 Samuel Lock, a London merchant, laid a large slab of black marble in the church under the altar bearing in bas-relief the following inscription:

"Here lieth the body of Christian, wife of Mr. Joshua Warren, sometime of this parish, merchant, the daughter of Samuel Avery, of London, Alderman, obit 23 June, 1669. Joshua, her husband, is also buried here."

Who these people were is a mystery, but Eleanor, the widow of the last Thomas Tey of Layer Hall, had re-married a certain Thomas Warren, and it is possible that Joshua was a descendant of hers.

During the century two new bells were given to the church. The fifth is inscribed: "Miles Graye made me, 1622;" the third, with

the same inscription, is dated 1673. "Miles Graye" represents a father and son of that name, both well-known bell-founders of

Colchester. (It is now thought more probable that the older Miles Graye was the grandfather, rather than the father, of the

younger Miles Graye, but this remains unconfirmed) In 1684 the church possessed a flagon and paten of pewter, both of which had disappeared twenty-three years later.

THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY.

THE MANOR OF LAYER-DE-LA-HAYE.

When Sir Edward Bettenson inherited Layer Hall from his grandfather in 1679 it was thoroughly mortgaged; but things grew gradually worse, with the result that in 1734 upon his death the family, whose motto was Que sera sera (What will be, will be), was obliged to hand the estate over to the owner of the mortgage, Colonel John Brown, of Huberts Hall, Harlow. Holman saw the manor house about this time, and described it as fairly large, lying on the right side of the road opposite the church with the Tey arms still in the windows.

Little is known of Colonel Brown except that he served under Marlborough and became a General in 1754. A map made in 1735 shows his Layer estate to consist of 744 acres divided into four farms:

The Hall Farm centering round the old manor house.

Junipers to the west with no farmhouse, now part of Garlands in Birch.

Damyons (clearly Damon's or Demmant's), now called the Rows.

Martins, with its farmhouse on the site of the Cross House.

There was a good road following the line of the existing footpath leading from the church to Layer Breton Heath past

William-a-Birches, which he also owned.

Nevards did not go with the rest of the Bettensons' estate, as it had previously been sold in 1724 to James Round, of Birch Hall. In 1745 it passed to his nephew, William, and afterwards to his son James, whose brother died in the Black Hole of Calcutta.

In 1756 General Brown made his will, desiring to be buried privately in Layer Churchyard, leaving £100 to the poor of the parish, and his manor to Lady Frances Burgoyne. In 1764 he died in France, and was buried in his garden, but in accordance with the will the body was subsequently brought to England through Manningtree, and reburied in a "handsome vault" at Layer. Whether the obelisk by the church door is over this vault or is merely a memorial is uncertain. It bears the inscription:

"To the memory of Lieut.-General Brown, whose military merit was founded under the auspices and confirmed by the approbation of John, Duke of Marlborough, and whose many private virtues and amiable qualities were long beloved and venerated and at last sincerely bewailed by all who enjoyed his friendship or were acquainted with the character of a humane, homely and honourable man, Lady Frances Burgoyne erected this monument as a testimony of his worth and of her own respect and gratitude."

The prophecy that if anybody should pick up one of the cannon balls from the obelisk a horse will jump out was probably invented later to deter naughty little boys.

In what way Lady Frances was linked with General Brown is not apparent. A daughter of the second Earl of Halifax, she had married Sir Roger Burgoyne, 6th Baronet, of Sutton, Bedfordshire, a cousin of the General who lost the War of American Independence.

Within three years of the old General's death his manor house, which had stood opposite the church for over three hundred years, was either burnt down or pulled down by its new owner; and the tenant farmer, Dan Rudkin, moved into the Cross House, which was named The Hall for the next eighty years. Morant says that the Tey arms were in the windows of this house also, but it seems unlikely.

Apart from the land which she actually owned, Lady Frances had manorial rights over certain freeholds belonging to other people. These were mainly isolated cottages on the Heath, which extended in 1767 from what is now the Vicarage drive to Bouncers Bridge (now Bounsted), and from the Roman River to the Birch-Abberton road. Balls Lane, New Cut, High Road, the Folley and Mill Lane were mere tracks across the common.

The black wooden cottage in the New Cut was the parish workhouse in 1767, and was conducted by the churchwardens. The property now called Heath House to the north of it, together with the thatched cottage adjoining, was called Bears-and-Martha's, and belonged to John King, a potash burner. Brickwall Farm by the village pond was built in 1767, but was named differently. In 1778 Ardleys in Balls Lane, together with the Harp and Tanyard opposite, was left by John Bridge to his daughter, Sarah Baker. Woodhouse Farm belonged in 1781 to a Mrs. Sturgeon of Stanway. Chestwood was named as now. Poor Wood (or Charity Wood) is named for the firewood it supplied to the five widows in St. Mary Magdalene's almshouses in Colchester under an old bequest. Each widow received forty faggots yearly, each faggot being worth fourpence.

In 1788 Lady Frances died, leaving the manor in trust for her surviving children. Her eldest son, Major General Sir John, had died at Madras in 1785, where he was in command of the 23rd Light Dragoons, the first detachment of European cavalry ever sent to India. His son, Sir Montague, was distinguished chiefly for having been summoned by his vicar under an old statute for not attending Divine Service for a year. Another descendant, Sir John, rescued the Empress Eugenie in his yacht in 1870.

Five years after the death of the testatrix the Burgoyne trustees sold the manor to Charles Western, of Felix Hall, Kelvedon, an Essex notability. His father was killed in a carriage accident, and his mother only saved the infant Charles by throwing him out of the window. Mr. Western was Whig M.P. first for Maldon and then for the County for forty-two years, and as the champion of the greatly injured Queen Caroline, and the spokesman of the farmer and agricultural labourer, was very popular locally. His tomb at Kelvedon says: "True to his Sovereign, zealous for the rights and interests of the people, foremost in every agricultural improvement, and a benevolent friend of the poor, his name will long be cherished with esteem and gratitude." His portrait is reproduced in the Essex Review.

Mr. Western never lived at Layer. When he bought it the estate was divided as now into two parts, the Hall and Cross Farms held together, and Layer Rows. Peter Clarke appears to have farmed all three. In the year of the French Revolution Mr. Western let the Hall Farm to James Buxton, who farmed it for forty years, and Layer Rows to John Grimwood, whose son and successor, John, lived there until 1850.

THE BERECHURCH HALL ESTATE.

The years which saw Sir Edward Bettenson in financial difficulties saw his neighbour at Berechurch in an even worse plight. Inheritor of the major part of his father's estate, Henry Audeley was a dissolute person who wasted his substance in riotous living. It was his habit to settle bits of land, usually the Rye, on his lady friends in London, and then to repudiate the gift. In 1708 his wife Elizabeth executed a deed stating that her husband had abandoned her, that she had no surviving children, and was dependent on her mother, Lady Strangeford, with whom she was living. This was followed by an Act of Parliament which limited Blind Knights, the Wick, Hill House Farm, and the tithe of Layer to Elizabeth for her lifetime. The Rye was already mortgaged with Berechurch to James Smythe of Upton. In 1714 Henry died in the Fleet Prison, where he was incarcerated for debt, and James Smythe became the owner of all the property not limited to Mrs. Audeley. Elizabeth generously sent £80 to save her husband from a pauper's grave, and Henry was thus buried "decently" in a huge tomb at Berechurch, but well away from the family vault. In the following year Francis Audeley, son of the Rev. John, former Vicar of Layer, put in a claim for what was left of the estate, but as nothing was left nobody took any notice. Upon Mrs. Audeley's death in 1732 at Chart, her jointure went with the rest to James Smythe.

The new lord of the manor, who was a great improvement on his predecessor, rebuilt Berechurch Hall, which had been destroyed by the anti-Catholic mob during the Civil War, and lived to enjoy his estate until 1741. A memorial to him may be seen in Berechurch. He was probably very old, because the property passed first to his great nephew, Sir Trafford Smythe, 4th Baronet, who died unmarried in 1765, and then to the latter's cousin, Sir Robert, fifth Baronet.

Morant described Sir Robert as "a worthy young man who is making great improvements to the house." By his marriage to Charlotte

Blake he had a son, Henry, and two daughters, both of whom married foreign noblemen. There is a memorial in Berechurch to one

of them, Louise Baroness Este. In 1787 Sir Robert had Lady Smythe and her children painted by Sir Joshua Reynolds.

This portrait, now in New York, is reproduced in the Essex Review. Sir Robert was M.P. for Colchester in 1784, and living at Berechurch, appears to have been a good landlord.

At the outbreak of the French Revolution he adopted revolutionary ideas and renounced his title. Stating that he "liked not the Government or climate of England," he went to live in Paris, as a banker. The Revolutionaries did not, however, reciprocate his liking for them, and in 1794 he was imprisoned, narrowly escaping the guillotine. He died in Paris in his bed in 1802, and is buried in Berechurch. The Harwich Customs officers refused to allow his coffin to enter England unopened lest it should contain contraband. As the local industry at that time was smuggling their suspicions were not unreasonable.

Sir Robert's Layer estate was divided into five farms and the Mill.

The Wick was farmed in 1735 by a certain John Pearson, whose only surviving son William was a freeholder in Layer, but died in 1777, leaving no children. From 1790-1795 the tenant was John Posford, who was succeeded first by his widow and afterwards by her second husband, William Theedham.

Hill Farm, which in 1767 was called Pilgrim's Farm-upon-the-Hill (after a family of that name) was let to another member of the Pearson family, John, who farmed it until his death in 1790, and also owned Layer Fields Farm. His widow, Sarah Pearson, farmed both for their son John.

Sir Robert's tenant at both Blind Knights and the Rye in 1790 was William Tracey, who died in 1799, and lies beneath a box tomb in the churchyard with a long illegible poem inscribed on either side. During this century tradition explained the name Blind Knights, by its having been a hospital for blinded Crusaders, but there is no written evidence of this earlier than Morant. It may, however, have formed part of the endowment of some such hospital or have belonged to some Knight (or even Mr. Knight!) who was blind.

The farm now called the Great House, which was probably identical with the Reveshall mentioned among Audeley properties in the 17th century, was in 1767 called Garlands. In 1839 it included a field called Saviours Grove, almost certainly that "bit of land lying below the Abbot's garden," which John Savare had given to the Abbey in 1305. By the 16th century this was called Sawyers and belonged to the Audeleys. It was clearly that part of Garlands which supplied the eightpence yearly for wax for the Rood. In view of the purpose of the bequest it is easy to see how it became corrupted to Saviours. There was a tollgate across the road immediately opposite the house, which was only removed within living memory, and may explain why the village divides so easily into two halves. This farm was let in 1790 to Thomas Tracey, the brother of William Tracey of Blind Knights and Rye.

The Mill, which is marked on a map of 1767, was let to Edward Willsmore.

Sir Robert's Court Rolls throw some light on the freeholds over which he had manorial rights:-

In 1736 Harvey's Farm belonged to John Sanders, who "built a malting office thereon," now known as The Granary, which gave the Malting Green its name. Dying in 1790, he was succeeded by his son John.

In 1767 George Wayland, a Peldon magnate, who had inherited Dukes Farm from Sarah Sadler, sold it to Nathaniel Whislay, who changed its name seven years later to Wellhouse Farm. The old barn remains, but the house was destroyed by fire a century ago.

Billetts Barn was left in 1770 by Charles Reynolds, of Peldon, to his grandson, William Powell, D.D., Master of St. John's College, Cambridge, and Archdeacon of Colchester, who died in 1790.

An adjoining field, Hubble Down, the major part of which lies in Peldon, was evidently considered worth having, for as early as 1594 Peldon folk, in a little rhyme about their fields, used to say:

"Hubble Down may wayr the crowne."

Another field close to Billetts is called Dove-House Field. This suggests that it was the site of the manorial or rectorial pigeonhouse, which, while providing its owner with nice dinners, was a great hardship to the neighbouring farmers.

In 1767 the shop between the Cross and Rye Lane belonged to Cornelius Micklefield, a butcher. The surname is interesting, for the ancestors of Cornelius, who were probably of Flemish origin, rejoiced in the name of Bathmichaelfell. This was too complicated for Layer people, and its corruption via Micklefield to Middlefield can be traced in the Registers.

In the same year the Forge Cottage, then called Mustow House, belonged to Francis Martin, whose tombstone bears the inscription:

"This man lived a social life beloved by all. Having no children of his own, he educated and put into the world thirty of his relatives."

This education must have been costly, for in 1769 there was no school of any kind in the parish. The history of this cottage and the forge can be traced through several hands until it passed to its present owner.

The first cottage on the left of Wellhouse Lane inscribed "J.G. 1791 S.G." was built by Joseph and Sarah Golding, of Birch.

The cottage at the south-east corner of the Malting Green dates from the middle of the century, and was built by Isaac Bannicks.

Other houses of some size were Prestneys, Fosters and Skitters, all called after families of those names. The houses may no longer exist, or they have changed their names, as they cannot be identified.

Among other freeholders in eighteenth-century Layer were John Sadler, Henry Cole, Stowers Carter, Charles Tiffin and Joseph Debnam (Demmant). Where they lived is a mystery, as in 1769 it was reported to the Bishop of London, in whose Diocese Layer lay: "The parish is not of large extent. It comprehends only about 25 farmhouses and cottages, and has neither Village, Hamlet or Family of Note in it."

THE CHURCH.

In 1732 Francis Canning died. His son Francis, who had married Bridget Goodall, of Abberton Hall, lived at Abberton Manor, and died in 1783, leaving an only son, John. Francis and Bridget are both buried at Berechurch. Since Francis Canning the elder and his sisters were Roman Catholics and Jacobites, and Anne his daughter was the Superior of the English Augustinian nuns in Paris (the only convent which survived the Revolution), it is probable that, although the younger Francis was married, buried and had two sons baptised according to the rites of the Church of England, the family were Catholics at heart, and consequently not much interested in their advowson of Layer; if indeed they were allowed to present at all. This may account for the number and confusion of incumbents during their patronage.

The eighteenth century Church was at a very low ebb. Many of the clergy were non-resident, and held several livings in plurality, providing curates to do their work at a low wage. In any case Layer with its stipend of £12 and its 25 houses, provided neither the wage nor the work for one man, so it was usually tacked on to a neighbouring parish, or offered to some poor clergyman holding an ill-paid position till something better offered. There were consequently frequent changes of minister, and during the whole century there was no parsonage house nor resident incumbent.

In 1700 the minister of Layer and Berechurch was Thomas Lufkin, who soon left to become Rector of Frating. The name of his successor is not known, but as the Berechurch registers record many marriages during the first half of the century in which both parties were Layer people, it may be assumed that both livings were held together. The changes of handwriting suggest a succession of several men.

The next recorded vicar was Christopher Gibbon, who began the existing Layer registers in 1755.

He was followed by Stephen Aldrich, B.A., of Emmanuel College, Cambridge, from 1755 till his death in 1769. He held Layer and Berechurch in plurality with Layer Breton. He married Miss Richardson, an apothecary's daughter, whom, it was reported, John Hopwood, of Stanway Hall, intended, had he survived, to make his second wife. In any case he had left her Stanway Hall and £10,000.

Aldrich employed eleven curates in fourteen years, of whom only the first and the last are of interest.

John Cantley, M.A., of Pembroke College, Cambridge, came in 1755, and helped on and off for twenty-three years. He died in 1797, and was buried at Messing, where a memorial says: "If sound sense and sincerity or a primeval simplicity of manners are held in estimation, the world hath here lost a friend."

Aldrich's last curate, John Stevenson, M.A., of Trinity College, Cambridge, who came in 1767, succeeded him as vicar of Layer and Berechurch in 1769 and was at the same time rector of Abberton. His handwriting suggests a scholarly and orderly person. Although he was Chaplain of Trinity and lived there, he signs the registers of all his three parishes fairly regularly, and must have spent long periods of his ministry in the neighbourhood. During his incumbency there was only one service a fortnight and three administrations of the Sacrament yearly, with about twenty communicants. Stevenson's standard for curates was not very high. He employed thirteen during the 18th century, none of whom were in any way noteworthy, and three of whom, to judge by the ill-kept registers, were almost illiterate.

In view of this confusion and neglect it is not surprising that the church building was allowed to decay, and that the earliest registers were lost. What is remarkable is that the late Jacobean and early Georgian registers survived until 1830, and that the existing ones go back as far as they do.

They are interesting. A search reveals the following unusual surnames:

Bunn, Bapah, Christmas, Cupid, Marriage, Wedlock, Yell, Drain, Farthing, Penny and Winkle.

Christian names for girls include: Amaretta, Matthew, Zilla, Zipporah, Keziah, Minerva.

For boys: Bonnitt, Spring, Easter, Mitte, Tristam, Easy and a magnificent roll of Old Testament names as Shadrack, Meshack, Abraham, Moses, Ephraim, Reuben, Uriah, Amos, Nathan, Zedekiah, Agur, Zachariah, Obadiah, Mordicai, Aaron and Job.

In 1728 was buried in the Quakers' burying ground at Copford Elizabeth Hood.

Thomas Ram, surgeon, was buried in 1777.

In 1784 "was baptised, Caravanna, daughter of Shadrack and Mesila Bainiell, travellers" (probably gypsies).

In 1781 Anne Cole died at the age of 100.

The first recorded church clerk was John Pottoly (1755-61).

In addition to the General's obelisk, there are in the churchyard six tombstones ante-dating the registers: Mary Prestney, 1719; Mr. Thomas Prestney, 1721; Elizabeth Harper, 1728; Abraham Tracey, 1730; Robert Pyott, Esq., 1733; and Bridget, wife of John Gooday, late of Boxted, gent., 1739.

A search of all available records discloses the following families to bear the oldest names in the village, though they are not in every case the descendants of their predecessors:

13th century: Clarke.

16th century: Digby.

17th century: King, Baker, Reeve and Cole.

1700-1740 : Theobal or Tibald (Theobald), Sadler, Boor (Bewers), Harrington, Round, Bland, Goody.

1740-1770: Carter, Demmant, Fisher, Gentry, Humm, Hellen, Kettle, Keable, Martin, Pooley (Polley), Peachey, Rudkin, Taylor, Tiffin, Walford, Willsmore.

1770-1800 : Atkinson, Barton, Bullock, Curtis, Mead, Pannel, Potter.

During the century two bells were added to the church, making five in all. The second, cast by Thomas Gardiner, of Sudbury, and containing eight silver coins of George I, is dated 1724. The first was cast sixty-eight years later by Mears, of London. As writers in 1710 and 1768 mention the existence of five bells, it is probable that these two were older bells re-cast. On the other hand tradition has it that all the existing bells were stolen from elsewhere.

John Dewhurst Vicar 1845-1869 and Elizabeth Dewhurst

THE NINETEENTH CENTURY.

THE MANOR OF LAYER-DE-LA-HAYE.

The early years of the century saw Mr. Western's tenant, James Buxton, farming Layer Hall, but living with his large family at the Cross House, which was considerably bigger than it is today. Traces of his farm buildings are still visible on the lawn in dry weather.

In 1807 in the course of a survey of the county the Board of Agriculture interviewed Mr. Buxton, who was evidently the principal farmer in Layer. He had "a threshing mill worked by three horses which threshes ten quarters of wheat a day. It does its work quite clean and far better than flails. . . . A man feeds, two women supply, a lad clears away the straw, and a boy drives." Threshing machines were novelties in 1807, and, like his landlord, Mr. Buxton was evidently very progressive. He stated that the land was exceedingly wet, and that although he had tried draining at half a rod asunder, no benefit resulted. Labourers' wages were 9s. 6d. a week, and were higher than at Berechurch. Women servants living in were paid £10 13s. yearly and girls £2. But food was cheaper than to-day. Beef 4½d. a pound, mutton 5d., pork 6d., butter 10½d., flour 2s. a peck, and potatoes 1s. 7d. a bushel. Working hours were from six to six, but piece-workers often worked from 4 a.m. to 8 p.m.

The privations suffered by the agricultural labourer are reflected in the Church registers, which disclose a terrible infant mortality during the years following the Napoleonic wars. Of the 67 deaths recorded between 1813 and 1825, 40 were infants.

When James Buxton died in 1828 Mr. Western let the Hall first to William Mays, and then in 1840 to Robert Ardlie Walford, who farmed it for 27 years.

In 1843, the year before his death, Lord Western, who had been made a Peer a decade earlier, sold the whole of his Layer property to Charles Gray Round, who was engaged at the time in re-building Birch Hall. Two years later Mr. Round bought Woodhouse Farm from Mary Brett, the daughter of Mrs. Sturgeon, and his heirs have owned the Manor of Layer Hall, together with Woodhouse and Nevards, to this day. When in 1846 the Cross House was partially destroyed by fire, Mr. Round re-built the manor house on its original site opposite the church. The front door is that of old Birch Hall.

Mr. Walford was succeeded in 1867 by his eldest son, William, who farmed the Hall until 1892, when it was let to Joseph Norfolk, whose family held it for thirty years.

When John Grimwood the younger died in 1850, Layer Rows was let to Sam Dennis, who farmed it until 1880, and was succeeded by his son William. Both this farm and the Hall were damaged by the earthquake in 1884. The widowed Mrs. Grimwood lived for some time in what was left of the Cross House, and her son James built the White Cottage.

The Court Rolls of this manor throw some light on the freeholds attached to it:

In 1827 Charity Wood was called Clevegrove, otherwise St. Mary's Grove, and belonged to Sir John Shaw, probably in trust for the Almshouses. In 1839 it belonged to the Rev. John Smythies in his capacity of governor. It is still called Charity Wood, but the logs no longer go to Colchester.

The workhouse survived until the establishment of the Stanway Union (which incidentally was built of bricks made behind the New Cut). Considering the weekly wage of 9s. 6d. in 1807, and the non-existence of pensions or insurance, one wonders how so small a house could hold all the people who must have needed such shelter as it afforded.

The four cottages at the south end of the New Cut were called Dyers in 1806, and were opened in 1827 as a public house called The Fox. But about 1839 the inn removed to its present site at the Cross, and Dyers became a private house once again.

Bear-and-Marthas retained its name until about the middle of the century.

The first Post Office was for many years in the house now named Brickwall Farm, the home of the Applebys. The house of which the present Post Office forms a part was the village bakery, and was called Wakelins. It was much larger than now, with a parallel wing on the north side, and consisted of nine tenements in 1839.

The history of Hurrells in the New Cut, so called from a family of that name, and now the home of Mr. Munson, can be traced as far back as 1802, when it was a carpenter's shop.

In 1827 Sarah Baker died, and Ardleys passed eventually to her grandson, Benjamin Baker, whose only son, Benjamin, the youngest of nine children, succeeded him in 1873 and died in 1909. This house has belonged to the Baker family for over a century. The Bakers also owned considerable property in the village.

The sixteenth century cottage known as Heath Cottage was in 1812 called Spicers. In that year William Salmon, who had bought it from Edward Ransom, died, leaving it to Susannah Cooper, whose husband sold it in 1835 by the changed name of Spencers to a porter merchant. As the lane passing the house was at that time the main road across the Heath, the Old Porter Shop, as it was then called, was excellently situated for its purpose. That there may be some connection between the porter and the smuggler's hole found there recently is not impossible. But the porter business moved to the newly built Donkey and Buskins in 1840. The true explanation of this unusual inn name seems to be that the son of Robert Gentry, the first licensee, went daily to the Bluecoat School wearing buskins and riding on a donkey. Donkeys are now extinct in Layer.

The Tiled House now the property of Mr. Harry Theobald dates at least from 1767.

Not until the Heath was enclosed in 1846 do we first hear of Eagles Eye, later Needles Eye, though it was considerably older. It belonged to Olivers until 1875, when Miss Harrison left it to William Baker, to whose family the land still belongs, though the house was pulled down early in the present century.

The Manor of Layer-de-la-Haye has thus remained intact for nine hundred and fifty years, and has belonged to ten families.

THE BERECHURCH HALL ESTATE.

Not so the Manors of Blind Knights and Rye, which, though united by Lord Audeley in the sixteenth century, were held together only for four hundred years.

In 1802 Sir George Henry Smythe, 6th and last baronet, succeeded his liberal-minded father. He was only eighteen; and had been sent down from Cambridge on account of "a row with a tradesman called Hiron." A typical Regency young man, a keen sportsman and devotee of the ring, he eventually settled down into great respectability, and was many times Member for Colchester. Unlike his father he was an extreme Conservative and a bigoted Protestant, but was, however, very popular locally.

It is related that at an election meeting a yokel called out: "Sir Henry, you're a fool, and we don't want a fool to represent us;" whereupon Sir Henry replied, "But, my dear sir, the fools want someone to represent them!"

His portrait in the Mayor's Parlour at the Town Hall shows an eminently respectable Early Victorian old gentleman. By his wife Eva Elmore he had an only child Charlotte, for whom he built the bathing shelter by the lake at Berechurch. Charlotte married Thomas White, of Weathersfield, and died in 1845. Her marble memorial stands beside the altar in Berechurch, where she is buried. When Sir Henry died seven years later his property passed to Thomas White, with whose death the Berechurch estate entered upon the last chequered fifty years of its existence as such. It passed first to the Formby family and then to 0. E. Coope, M.P., who re-built the house. Its last owner was Mrs. Hetherington; and after the War it was broken up, the Layer manors and farms being sold separately to their present owners.

In 1803 Sir George Henry wrote to a friend in London: "We are in great alarm here about the invasion. All the farmer volunteers are ready to march at an hour's notice, and a great many people are going to leave the roundabouts of Colchester to come to London, among whom I believe is Mrs. Canning."

The lady to whom he refers was the widowed Mrs. Canning, of Abberton Manor, who had just lost her only son John on a passage from India, and as she was nearly seventy she may be forgiven for going to London to seek greater security. She died in 1823, and Abberton, with the advowson of Layer, passed through the marriage of her only descendent Bridget Canning, to John Bawtree, a Colchester banker.

The whole countryside was indeed in a state of nervous tension over the threatened French invasion. A beacon was erected at Wigborough, and telegraphs were prepared on church towers for signalling. The Cheshire Militia were camped on Langenhoe Common, and one would gladly picture James Buxton and the other Layer farmers drilling to defend the marshes against Napoleon. The truth is, however, that the Roll of Volunteers in Colchester Castle is signed by only three Layer men, John Chaplin, Jonas Fisher and John Davis, none of them freeholders.

By 1811 John Pearson the second had taken over Fields and Hill Farms from his widowed mother, and seems to have been a very successful farmer, for in 1827 he bought Wellhouse Farm and Lower End from the heirs of Nathaniel Whislay. He also leased Blind Knights and the Wick for some years, and in 1836 was farming altogether, either as owner or tenant, five separate farms. In 1839 he owned the tithe of Layer, which he had probably bought from Sir George Henry. This was then worth £680, out of which he paid the incumbent £12. The tithe has long since been sold, and is still in lay-hands, but the charge of £12 still remains on Fields Farm, and is, in fact, the only portion of the stipend derived from within the parish. In 1906 Mrs. Hetherington, as the largest tithepayer in Layer, agreed with the titheowner, Mr. Hempson, to undertake his whole liability for the upkeep of the chancel in lieu of paying tithe. Consequently all land in Layer formerly her property is now tithe-free, but the owners are liable for the repairs of the chancel in proportion to the rateable value of their holding.

When John Pearson died in 1852 his family left the village, and sold Fields Farm and Wellhouse to John Parmenter, who owned them until his death in 1872. He was succeeded by Edwin Walford, second son of Robert Ardlie Walford of Layer Hall, whose family farmed them until 1918.

John Pearson relinquished his tenancy of Hill Farm in 1836, and was succeeded there by Abraham Dakins, who also held Chaise House, afterwards called Dog Kennels House, and now erroneously, Well House. Abraham's widow, Susan, farmed it from 1842-1872, when it was once again united to Fields Farm by Edwin Walford. Thus it happens that this farm has thrice been farmed by ladies, Mrs. Pearson, Mrs. Dakins and the present owner, for periods amounting in all to nearly fifty years.

When William Tracey died in 1799 Blind Knights and the Rye were let separately to William Harvey and Sam Pettican. A contemporary map shows a good road joining the two farms, relict of their previous single owner.

When William Harvey's lease terminated in 1820, Blind Knights was joined to Fields Farm for awhile under John Pearson, but was again let separately in 1836. In 1854 it was let to William Richardson, who farmed it for thirty years.

In 1823 Thomas Tracey relinquished Garlands to follow his brother William at the Rye, where his son John succeeded him until his own retirement in 1854. One hundred and thirty-one years elapsed between the birth of Thomas and the death of John. These two old gentlemen were followed by William Richardson, of Blind Knights; and both farms were again joined for thirty years.

When Thomas Tracey left Garlands he was followed there by Martha Syred till her death in 1839. In her time this farm lost its old name, and became the Gate House, from the tollgate there. She was succeeded by members of the Royce family, who, first as tenants and then as owners, farmed it for nearly ninety years. About 1890 the name was again changed to the Great House.

In the year of Waterloo, Sam Posford, the son of the former tenant, farmed the Wick. John Pearson followed in 1836, but three years later it was let with Billetts to Charles Hall. In 1852 he was succeeded by James Pertwee, who lived there for twenty-two years. At the end of the century Billets was known as Botany.

In the early nineteenth century the Mill was a desolate place. There was no through road, and the lane was a mere track across the surrounding heath. The millers were successively: Dan Cooper until 1826, John Royce for forty-four years and Joseph Norfolk for another twenty.

The Kiln was built about 1800 on land belonging to the Berechurch estate, and was let to members of the Gentry family. There was another brickfield at the south end of the New Cut whence came the bricks for the Stanway Union House.

Of the freeholds on Blind Knights Manor the chief after Fields Farm was Harveys. John Sanders, the second, died in 1803, and his son John was evidently not a successful maltster, for in 1816 he made a present of it to his own son Evatt, to whose wife's father, John Poynter, it was mortgaged. Evatt succeeded in paying off the mortgage and died in 1852, leaving it to his daughter, Martha, and then his son Alfred. It remained in the family until 1911.

By 1839 Mr. Micklefields' shop had passed to Sam Pettican, the former tenant of Rye, and it continued as the butcher's shop for many years.

Early in the century William Harvey bought Mustow House from Richard Smith, and it remained in his family until 1901, when the last of the Harveys disappeared from the annals of Layer after owning land for at least five hundred years. The Nevards, however, who first appeared in the village in the fourteenth century and survived until 1819, ran them very close. But the Clarkes have been in Layer since the thirteenth century, and are still there. They therefore hold the record.

The only farm in the village not forming part of either Manor is Aldenham Oak. In 1839 it was much larger than now, and belonged to James Coleman. By 1888 it was considerably reduced in size, and was called Burnt Downs. One may therefore assume that there had been a fire. The present name is quite modern.

THE CHURCH.

The early nineteenth century saw the continued ecclesiastical confusion of the eighteenth. John Stevenson was Vicar of Layer until 1826, and continued to live mainly at Trinity College, Cambridge, and employ curates. He seems to have come to some arrangement with John Dakins, the Rector of St. James, Colchester, to supply officiating ministers in his absence. Curates were one of Dakins' specialities. At this time he was also providing them for Abberton, Peldon, Berechurch, Virley, Salcot and Wigborough from his own staff at St. James, and when there were not enough to go round he officiated himself. Unlike the absentee Rector of Peldon, Jehoshophat Mountain, who was simultaneously Rector of Montreal in Canada, where he lived and died, John Stevenson does not appear to have been neglectful; and towards the end of his life he lived in Abberton, where he was buried in 1830. In any case there was no parsonage house in Layer.

Of the eleven curates whom Dakins sent out to Layer during the first quarter of the century little is known, and six are merely names. But five of them seem to have turned out better than those chosen by the Vicar himself in the early years of his incumbency.

Edward Crosse, the headmaster of the Grammar School, officiated for two years, and was later destined to succeed Stevenson as vicar.

William Plume afterwards went to Boxford, where he coached some of the earliest C.M.S. missionaries.

John Clarryvince later became headmaster of Earls Colne Grammar School.

Vicesimus Torriano, whose name implies that he was a twentieth child, was subsequently rector of East Donyland, where he built the present church.

To Meshack Seaman, who ministered to Layer in 1825, and eventually succeeded Dakins as Rector of St. James, we are indebted for two reasons: He inaugurated a "Ministers' Book," a valuable source of information about nineteenth century church services; and he left his Bible to Layer Church when he died in 1872. This Bible bears his name, and there are dates to suggest that he read it through from beginning to end during the last year of his life.

During his ministry Layer began a long connection with the Church Missionary Society. In 1825 William Marsh, Vicar of St. Peter's, preached in Layer Church on the Society's behalf, and obtained a collection of nearly £5, a very large offertory for those days. In the same year three young clergymen officiated at a number of services. These were among the first missionaries to Sierra Leone, then known justly as "the white man's grave" owing to the awful climate.

William Betts, of Colchester, was one of William Plume's students from Boxford. One of the first to enter the C.M.S. College at Islington, he was ordained in 1825, and after ministering at Layer for a few months he sailed to Africa in 1826 with his bride, Mary Paul, who died three months after leaving England. He returned on furlough in 1827, 1831, and 1833, coming to Layer each time, and finally went to Jamaica with his second wife, the widow of another West African missionary. She died in 1838, but he survived until 1865.

Alfred Scholding, a Suffolk man, was an officer in the East India Company's Navy. At Islington and ordained with Betts, he sailed with Mr. and Mrs. Betts for Sierra Leone, together with his own bride, Hephzibah Wagstaffe. She died within a few days of Mary Betts, and Alfred returning broken-hearted to England three months later, died on the voyage.

James Norman was a little older and had worked for four years in Sierra Leone before his ordination in 1825. He officiated at Layer from time to time until 1826, when he sailed for Australia, where his wife, Judith Wright, died within three years. One would like to know more of Mary, Hephzibah and Judith, and whether they ever worshipped in Layer Church with their husbands.

When John Stevenson retired in 1826 after an incumbency of 57 years (he retained Abberton until 1830), his former curate, Edward Crosse, M.A., succeeded him. He held Layer, for which he received £82, in plurality with Berechurch, inaugurating a connection which was to last for eighty-seven years. Since he was also headmaster of the Grammar School it is no surprise to find that he employed eight curates in nine years, among whom were Robert Morrell, afterwards Rector of Woodham Mortimer, Thomas Rogers, the second master at the Grammar School, and William Wright, D.C.L., a later headmaster. Edward Crosse seems to have been zealous and conscientious, and finding many of his parishioners unbaptised (and no wonder !), he held a number of adult baptisms. A memorial in Berechurch says that he died in 1835 at the age of sixty-one.

His successor was Matthew Dawson Duffield, B.D., who lived at Park Farm, Berechurch, and came to Layer when required. During his incumbency the parish sustained the loss of the Registers of 1678-1752, which went to light somebody's kitchen fire, but gained the school which was built in 1837, and given to the Vicar and Churchwardens "for the education of the poor children of the parish in the principles of true religion and useful knowledge." It is not known who gave it, but the site suggests Lord Western. There used also to be a Methodist School in one of the cottages adjoining the Great House. Mr. Duffield resigned in 1842, and eventually became a Canon and chaplain to the old Duke of Cambridge. When it was not convenient to officiate at Layer, he employed other people's curates, among whom was one afterwards to become even more important than the Rev. Matthew himself.

This was Robert Eden, of Christ Church, Oxford, whose father was a well known writer on economics, and whose grandfather had been Governor of Maryland. He was at this time curate of Peldon, where he lived in the rectory, and was a friend of John Griggs, of Messing Park, who left it to him in 1839. In 1837 he was Rector of Leigh, and at the age of forty-seven became first Bishop of Moray, Ross and Caithness.

"He gave up a living worth £600 for a position of which the emoluments were £150 and no house. His pro-cathedral was a cottage fitted up as a mission chapel on the banks of the Ness. During his tenure he quadrupled the income of the See and founded Inverness Cathedral. His bonhomie and love of telling jocose stories scared strict spirits, but his grand manner was very telling. Theologically he was a moderate High Churchman, politically an uncompromising Tory."

Inverness Cathedral was, with the exception of St. Paul's, the first post-Reformation cathedral to be built in the British Isles. Eden ended up Primus of the Church of Scotland. One wonders how his uncompromising Toryism, his High Churchmanship, and his grand manner went down in Layer in 1837.

When Mr. Duffield resigned in 1842 he was succeeded by John Richard Errington, M.A., an Oxford man, who came from Spring Gardens Chapel, London, at the age of 34. He left in 1845, and afterwards became Vicar of Ashbourne, Derbyshire, and later Rector of Ladbroke, Warwickshire, where he restored the church, built the school, and was much loved by his parishioners. His grave at Ladbroke bears the inscription:

"John Richard Errington, M.A., Rector of this parish from 1872 to 1882. Born September 27th, 1808. Entered into his rest October 4th, 1882."

At one time he was chaplain to George Tomlinson, first Bishop of Gibraltar, who preached in Layer Church during Mr. Errington's ministry.

Of the many neighbouring clergy who officiated in Layer during the early nineteenth century, the most noteworthy was Charles Hewitt, Rector of Greenstead, who was no teetotaller and apt to fall asleep in the pulpit. On one such occasion, waking suddenly and finding himself alone, the clerk, meaning to inform him that the congregation had departed, said, "They're all out, sir;" whereupon Hewitt replied, "All out? Then fill 'em all up again!" He was once headmaster of the Grammar School, and was described as "a gentleman who paid no attention to the duties of schoolmaster."

In 1845 the first resident incumbent for many years was appointed in the person of John Heyliger Dewhurst, M.A., at the age of thirty-six, an Oxford man, and the son of Edward Dewhurst, of St. Croix, West Indies. In 1846, Charles Gray Round gave his share of the newly-enclosed Heath as a site for a new parsonage, and he probably built the house itself also. Mr. and Mrs. Dewhurst (her name was Elizabeth) lived there for twenty-three years, in which time five children were born to them, one of whom lies in the churchyard. The stipend was increased by the Ecclesiastical Commissioners to £110.

The energy and earnestness of the new Vicar, who was an austere but very just man, soon made itself felt, and the congregation became too large for the church. The population had nearly doubled itself in the previous half-century, and the number of houses had risen from 25 to 113. He found the fabric of the church in a bad state, and in 1848, with the aid of a grant of £85 from the Church Building Society, he set about enlarging and restoring it. Beyond the fact that by the addition of the south aisle, free seating for 140 persons was provided, there are no records of this restoration. What happened to the windows and monuments on the original south wall, or who paid the rest of the bill is not known. It is perhaps further evidence of the generosity of the Lord of the Manor.

About 1852, John Pearson, as titheowner, re-roofed the chancel and lined it with cement, thereby covering all tombs on the walls

except that of Thomas Tey. To strengthen the wall further he blocked a south window and door, and renewed the east window.